Little Thing

Ewan Downie

The baby was three days old and still unnamed before they let anyone touch it.

That first night, after the birth, they lay in bed, bodies curved around their new baby: the tiny clenched face, the red soft fists; them unsleeping, all the lights left on, because they were afraid they’d roll over and crush it.

Through all the next day, everything incandescent. Her body empty, shedding its lining, trembling as the womb retracted. He, staggered, confronted with the thing they’d made, its snuffles and animal panting, its squeaks and cries and grunting roars, its wrinkled face, its raw skin, the tiny fingers, the tiny toes, nails like slips of wax, her skin so crumpled. It’s a girl.

Both of their mothers have been here since the birth, and it is now three days later, and neither one of these new grandmothers has held, or even touched, the child.

* * *

She has seen the baby born. The tiny squalling bundle taken from the pool, lifted like an effigy, wiped by green-gowned midwives, weighed, and handed to the parents. Her son and his wife, their faces broken by the thing they’ve made. Both so young.

She is second place, she knows that. As mother of the father, she is subordinate. When labour started, they called the mother’s mother first, her mother arrived first.

She’s waited three days, while the couple fuss, and take naps, and coo over the child, and fumblingly learn how to change nappies streaked with black meconium, and discuss whether and how they should bathe the baby, and she has held her tongue while the other grandmother hovers like a vulture, stretching her withered neck, always nearer to the baby than she is, always just faster to respond.

They are in the living room, and she is sitting on one of the two cluttered and uncomfortable couches that are placed at right angles to each other. The couches are covered with mismatched ethnic cushions from trips her son and his wife have taken to places far away. Scarves, and cushions with little circular mirrors sewn into them, everything tassled, everything gaudy in bright colours, pink, and salmon orange, and electric blue.

The new mother is slumped on the other couch, with the baby lying sideways on her knees, sleeping, the back of its head cupped in one of the new mother’s hands. The new mother is looking down at her new daughter’s face. The mother looks like a child, like a little girl wearing her parents’ oversized shoes, an idiotic expression on her face. She is holding the baby’s head wrongly, so the head tips slightly back, exposing the soft throat.

The grandmother wants to lean forward from the couch and correct the angle of the mother’s hand, to right the baby’s neck. But she doesn’t. She could just lean forward and touch the baby. But she doesn’t.

Her son is somewhere in the house, and the other grandmother is sitting at the table in the bay window of the sitting room, and looking out into the street, leaning her forearms onto the half-done puzzle that is laid out on the table.

It infuriates her, how long that woman sits there, staring into space, not putting one piece in the puzzle. But she realizes that for once she is nearer to the baby than the other grandmother, and she tries not to breathe.

The puzzle is a hard one, 1000 pieces, a picture of a forest glade, with an oak spreading its gnarled, mossy trunk, and thick knuckled branches, and sprays of thin twigs tipped with bright new leaves, over a grassy dell, in which stands a dappled faun, its thin neck turned, looking to the forest behind it, ready to run. She has been working on the puzzle when she can, but it has been hard to concentrate, always watching for what the other grandmother is doing, and pretending not to watch. She must not stand too near the baby, or stay too long near the baby, or that woman will appear, and insert herself just subtly closer to the baby than she is, and yet whenever she isn’t near the baby she knows she’s missing out, she’s falling behind, in some obscure race in which the prize is love.

Then the other grandmother looks up from where she sits at the table by the window and sees her closer to the baby and the mother and says, apropos of nothing, “I could hold her,” as if she’s just thought of it, as if it’s just occurred to her now, this second. The other grandmother’s voice is very smooth and calm, but she can hear the greed behind the words. The hunger. And the triumph. The other grandmother knows that she will get her way. She will be first.

And she thinks that this is right, that the mother of the mother should hold the baby first, but she hears herself say, “I’m closer. Don’t get up.”

And she finds herself moving across to the other couch beside the mother, who lurches as if to stand, her eyes wide, staring, trying to get away, but also trying not to wake the baby.

And she slides in neatly beside the mother and lifts the soft, warm bundle out of the stunned mother’s arms, and presses the baby to her chest.

And now the other grandmother is standing behind the couch frozen, looking down at her, gaping like a fish, and the young mother is staring at her, eyes bright with horror.

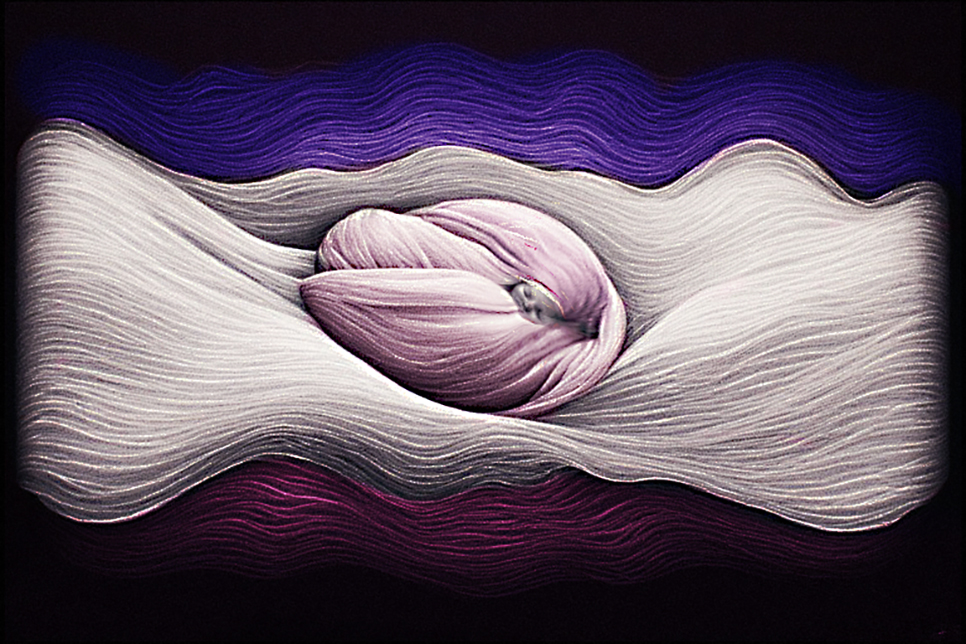

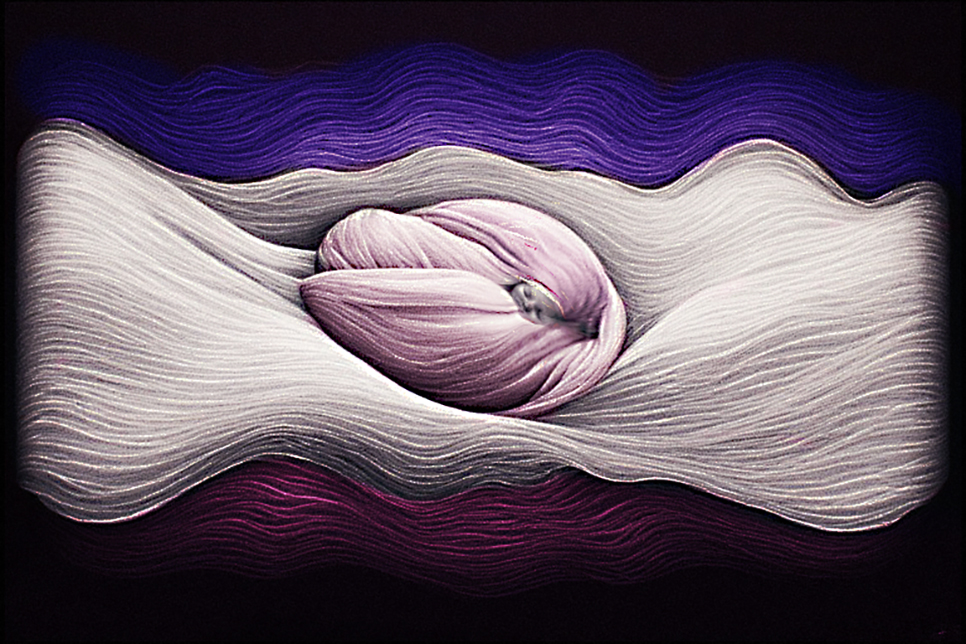

But she turns away from them and gazes into the deep powder blue eyes of her new granddaughter. The folded face, the reddish skin, the eyes closed, hands bunched in soft fists, so small, tiny fingers with surprisingly long nails, nails soft and flexible like hair, the hair surprisingly thick, surprisingly black, surprisingly long. She’s so light.

There is an explosion of warmth in her throat and in her belly, like she’s clasping a hot water bottle in a cold bed at night, a cold bed where she lies alone, and she kisses the top of her new granddaughter’s head, and feels against her lips the almost-nothing fuzz of thin, dark, newborn hair, the smell, like no other, spicy, sweet. She holds the baby close, and a thrumming starts, and grows until it engulfs everything, and she thinks I did it, I did it. She kisses those tiny lips, those tiny ears, and makes small wordless sounds, and speaks to the baby, “I could just eat you up. My little crumb, my darling, there, there, there,” she says in a whispering, simpering, goo goo voice.

And she hears herself say, “Aren’t you so beautiful? Oh. I love you, little thing.”

And she thinks how empty those words are. How meaningless that word is. “Love.” There is something disgusting in it, she thinks, something rank. The lady doth protest too much, she thinks. And she thinks how easily some people speak that word. “Love.” When they want to get something. When they want to make you do something, how easily they say “love.” When they want to trick you. The other grandmother says it. And her son’s new wife says it to him all the time, so now her son says it too. “Love. Love.”

“Love,” she hears herself say. “Love. Love.”

She looks up.

The other grandmother and the mother, her son’s young wife, are staring at her, both leaning slightly forward, as if they thought to take the baby from her, but stopped themselves at the last moment. Their eyes are very bright, but they do not look at her eyes, they look at the thing she holds, and she holds out that thing towards them, towards the other grandmother.

“Here,” she says. “You take her.”

And the other grandmother leans over the back of the couch and takes the baby.

And she becomes afraid of what she’s done. She sees the future. Where she will not be part of this child’s life. Where her son and his new wife shut her out. Where she’ll be just a name, barely a face, in her only granddaughter’s life. And she stumbles from the room, her face hot, her eyes burning, into the hall that divides up the rooms of this inconvenient house, where the doors open the wrong way, into the kitchen where her son looks up from reading the paper, and she does not know what to say to him, and she has no idea what to do.

* * *

The new mother and her mother sit on the couch with the baby between them, and the new father comes in, and sits on the couch across from them.

And the incandescence has dimmed, or else their eyes have grown used to it.

And the new father says, “My mum’s gone out.”

And the new grandmother, the mother’s mother, says, “So. What are you going to call her?”

Table of Contents

|